When the frantic upside-down world spins out of control around Katie Paccione ’12, she knows exactly how to slow it down. She goes upside down and spins with it.

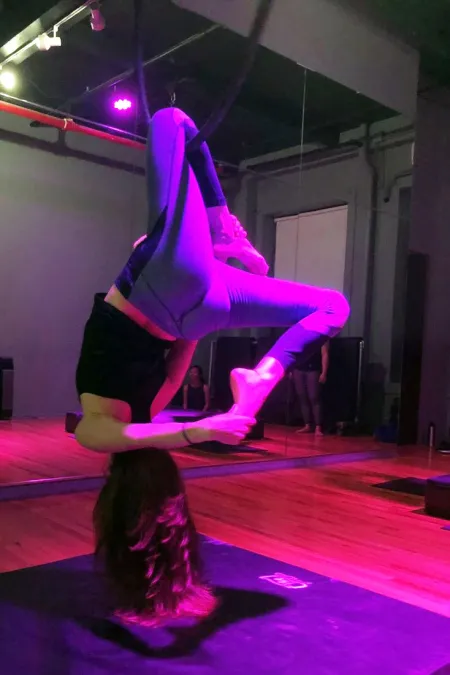

Isolated in her living room, she trades in a three-ring circus of a global pandemic for one ring: a hula-hoop on steroids dangling from the ceiling of her Bronx apartment. Hanging out in an Ithaca College T-shirt, heather gray like the sky outside, the aerialist spins slowly. Fridge, couch, TV, table, fridge, couch, TV, table. Like most of us, she’s recalling a life “before all of this happened.”

After a grueling lead up to a live aerial performance that had been just days away, her final rehearsal had fallen on “The Ides of March.” The next day, her studio closed along with much of New York. The show must not go on.

Somehow, even that crushing disappointment still feels better than quarantine, so today she again cues up the song from her canceled act and starts into her routine. She and the haunting song hang in the air like fog. The classic rock hit has been slowed to a crawl and covered by a soulful, breathy woman, “Every breath you take, every move you make, I’ll be watching you.”