As the murder of George Floyd has prompted a reexamination of racism throughout society, a group of Black musicians, composers and educators is calling for change in one of the nation’s least racially diverse institutions: the American orchestra.

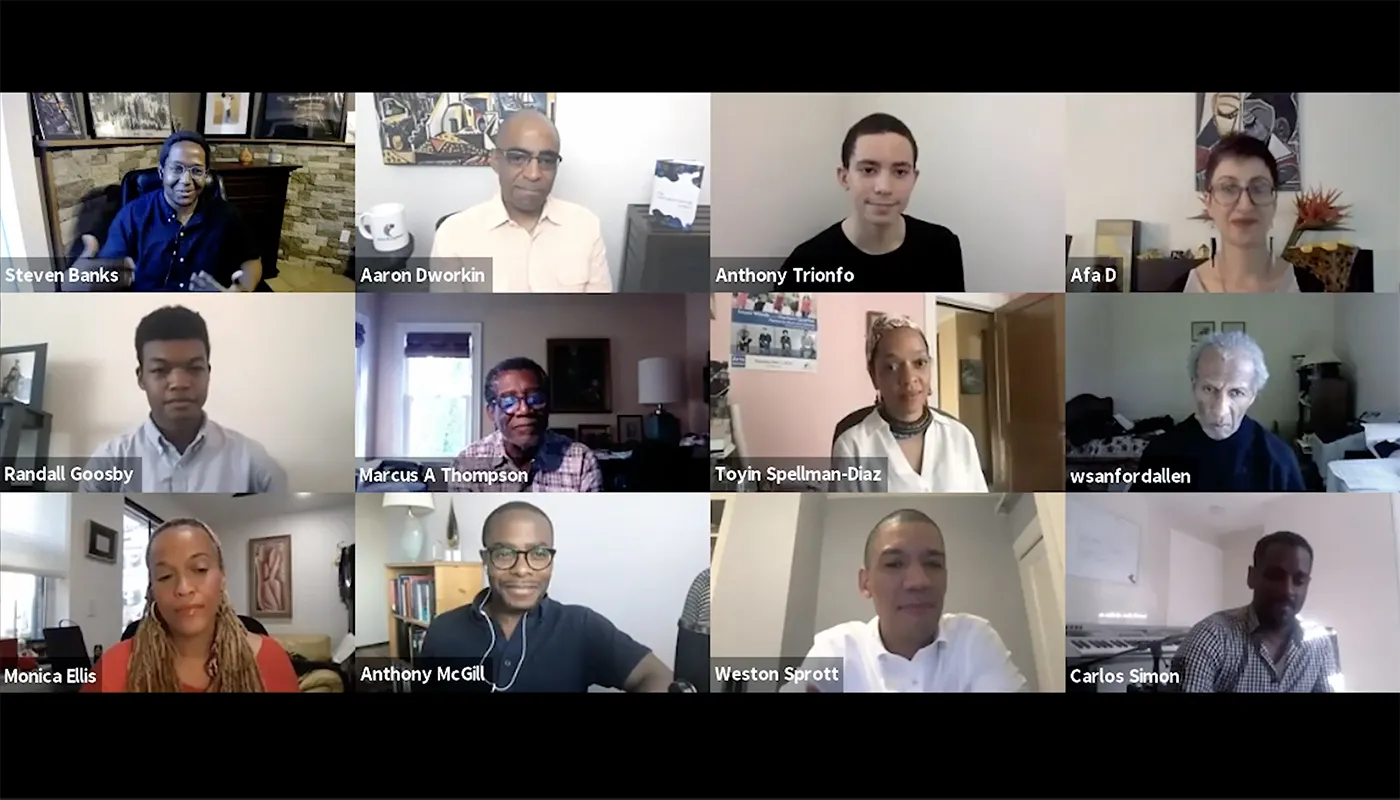

Steven Banks, an assistant professor of saxophone at Ithaca College, helped organize a panel discussion on the experience of Black musicians in the classical music world on June 10. The online panel, recorded on Facebook, has attracted more than 81,000 views since it was posted.

“The society that we live in has to become less systemically racist in order for the entirety of our country to take steps forward,” said Banks, a classical saxophonist who performs around the country. “Even though we may feel classical music is removed from this, I definitely think that there’s a lot of overlap.”