Food pundits and celebrity chefs often put forth a narrative that growing your own vegetables and cooking meals from scratch can help cure many of society’s ills — everything from childhood obesity to environmental degradation. Joslyn Brenton, an assistant professor in Ithaca College’s Department of Sociology, disagrees.

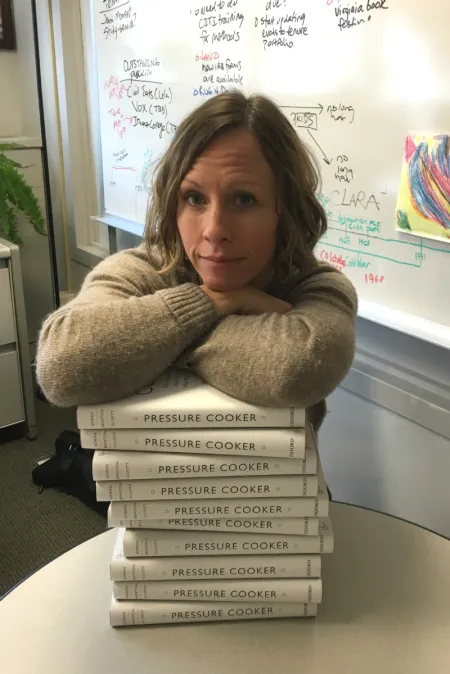

In the new book “Pressure Cooker: Why Home Cooking Won’t Solve Our Problems and What We Can Do About It,” Brenton and her co-authors, North Carolina State University associate professor Sarah Bowen and University of British Columbia assistant professor Sinikka Elliott, argue that positioning family meals as the answer to social problems is inadequate and places a disproportionate burden on families and mothers.

The book is based on over 150 interviews the authors and their research team conducted with an economically and racially diverse group of mothers, as well as over 250 hours of fieldwork — time spent observing families cook and eat, and tagging along with them to the grocery store.

IC News spoke with Brenton about her book and the problem with positioning home-cooked meals as a solution to pressing social problems.

IC NEWS: The idea that home cooking can solve issues like childhood obesity is prevalent among food pundits like Jamie Oliver and Michael Pollan. What’s wrong with that message?

BRENTON: We have quotes from Jamie Oliver and Michael Pollan in our book. And we’re doing something that’s a little dangerous because Michael Pollan’s message resonates with a lot of people. And I get it. I’ve read his books. He’s a compelling writer and he cares about the food system. Jamie Oliver is quite the character, and he’s very charismatic. But both of those guys, and others like them — what we call food pundits and food experts — they’re giving us the same message: if we slow down, if we prioritize food in our lives, if we just take the time to care and get back in the kitchen, everything’s going to be better. We don’t find that at all.

As we discuss in the book, that is a lovely idea, but that is not how people’s lives work in reality. So that can’t be the solution to our food dilemmas. And we do have food dilemmas. Many people in the country experience food insecurity. We have a food system that’s not sustainable and that is downright unsafe at times, and we have high rates of food-related illnesses. These are important issues, but “slow down and try harder” is actually not going to get us out of this problem. What we’re looking at in the book are structural inequalities and how they shape people’s lives and what they eat. We wanted to know how diverse mothers of young children think about food and how they see their own relationship to food. What we find is a complex picture, and that’s sometimes hard to work with.