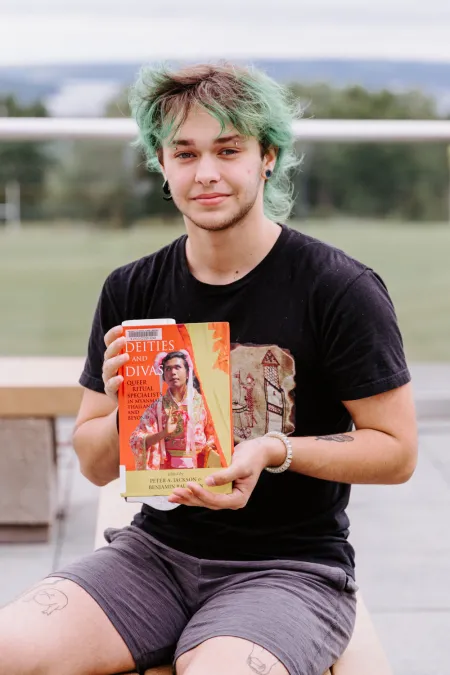

In a studio space in the Ceracche Center, Vic ’26—who only uses their first name for their art—built a robot from empty LaCroix cans. In a lab across campus, Sofia Gross ’27 analyzed variation in the owl genome. In a coffee shop in downtown Ithaca, Zoe Gainer ’25 prepared a questionnaire to survey autistic college students about the barriers they experience in the transition to college life. And with his pet bearded lizard nestled in his palm, Frankie Valens ’26 pored through books and media exploring gender expression in Burmese rituals.

Each of the 35 students in this year’s Summer Scholars Program cohort pursued a line of inquiry that was complex, open-ended, and entirely their own—but they didn’t do it alone. With support from faculty mentors and funding from Ithaca College’s Summer Scholars Program in the School of Humanities and Sciences, they spent the summer doing exactly what scholars do: engaging their curiosity, investigating real-world problems, and uncovering insights—while getting paid for their work.