When the phone rang at 3:00 AM, we knew it was Rome, something disastrous enough to make Uncle Tonino ignore the six-hour time difference. Jolted awake, we braced ourselves for a car accident or a cancer diagnosis. With racing hearts, we gathered around the phone as Papa barked into the receiver: “Pronto!” Four thousand miles away, Tonino’s voice was tinny and shrill: “Buonino!” he spluttered, using Papa’s boyhood name. “The barbarians have returned!” My God, what had happened? Had a lunatic vandalized another Michelangelo? Had the Red Brigade executed another premier? Had the PLO hijacked another cruiser? Worse, moaned Tonino. A McDonald’s was opening in the Piazza di Spagna!

I gasped and sank to the floor. So my boss had been right, after all. Two weeks ago, while working late at our small ad agency in North Plainfield, New Jersey, he had informed me that the Golden Arches had built its first outlet in Italy. “Maybe they’ll serve McPasta,” he teased. Alarmed, I phoned my uncle the next day. “Bolzano,” he confirmed, speaking with the confidence of a retired business journalist. “Southern Tyrol. Lots of Austrians. They want beetroot, not relish, with their burgers! Believe me, this will never catch on.”

When I conveyed these assurances, my boss shook his head and flashed a Cheshire grin. “Look,” he said, counting his fingers, “they’ve conquered Germany, they’ve conquered Japan, so why shouldn’t they conquer Italy? You the only former Axis Power stronger than the Big Mac? Bullshit. They’ll be in Rome before the end of the year. Right in the Forum.”

His smugness infuriated me. “Impossible!” I blurted. “The monuments, the zoning—!”

“They’ll get around it,” he purred. “They always do. You can’t stop progress.”

Quivering, I stood and faced him. “No hamburger chain will ever capture Rome!” I said. “The Capitoline geese will prevent it!” My accent had become incomprehensible, so the boss asked me to repeat the challenge and to explain the reference. When Rome was abandoned to invading Gauls, a hilltop garrison was warned of intruders by the geese squawking in the Temple of Juno. Though deprived of food, the soldiers had rather starved than eat these sacred birds.

The boss was unimpressed. “They can squawk all they want,” he said. “Those geese will be ground into Chicken McNuggets.”

Indeed, they had. Povero zio.

Papa blistered Tonino’s ear with profanity. Was this his idea of a fucking joke? I calmed Papa, pried the receiver from his hand, and consoled my uncle, who sounded as if he had been kicked in the gut. After he recovered, I asked how McDonald’s had by-passed the Ufficio Speciale per gli Interventi sul Centro Storico (USICS), the Special Office for the Management of Rome’s Historic Center. Diplomacy, Tonino replied. The architects from the Oak Grove, Illinois headquarters had designed a more subdued façade and had set new standards for interior décor. Toninio had seen the prototype at the city council meeting. Some fine Italian hand must have suggested certain touches. The paneled walls were made of olive wood and ceramic tile. The salad bar was bigger than a gondola and included puntarella, Rome’s native strand of wild chicory, whose twisted wiry shoots resemble Bernini’s Baldacchino in St. Peter’s. The same photographer who had taken John Paul XXIII’s picture for Life, it was noted, had done the bronze-framed portrait of McDonald’s founder Ray Kroc. Prompted by the Holy Father’s memory, the politicians, businessmen, and spectators applauded, drowning out objections from the city planners, engineers, and historians. The ribbon-cutting would occur in four months.

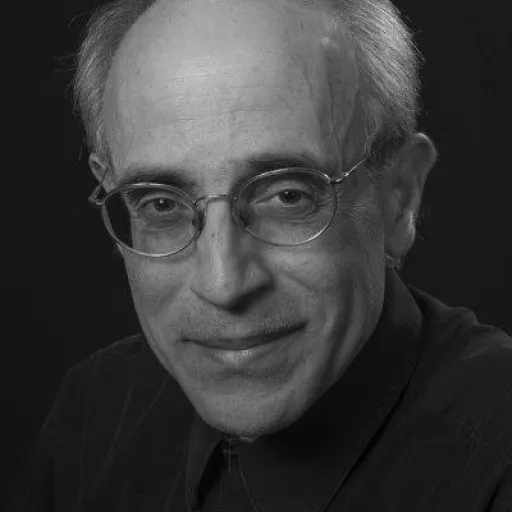

Flabbergasted, Toninio studied Ray Kroc’s triumphant face, the face of a bully and a vulgarian. This hamburger king should have been cast as Trimlachio in Fellini’s Satyricon, not Mario Romagnoli, the proprietor of Tonino’s favorite trattoria Al Moro. Located near the Trevi Fountain, it served the best spaghetti carbonara. After the zoning fiasco, Tonino got drunk there.

“Kroc,” he muttered. “What kind of name is that? Doesn’t it mean ‘liar’?”

“That’s crook,” I corrected.

“No, no, no! When Americans accuse someone of lying, they say, ‘That’s a Kroc!’”

“You’re thinking of crock. C-r-o-c-k. Broken crockery. If a claim can’t hold water—”

“It’s a crock. Exactly!” pounced Tonino. “This Kroc is a liar!”