For the first eleven years of my childhood, I religiously watched The Ed Sullivan Show on CBS Sunday evenings at eight. And I mean religiously, for to my first-generation Italian eyes Ed Sullivan was not a variety show but the Apocalypse of Ellis Island as staged by P. T. Barnum: Tyrolese yodelers decked in lederhosen wooing plastic cattle; Venetian gondoliers crying barcarolles in cardboard gondolas beside a kiddie pool; Sardinian gypsies dancing the tarantella with wild abandon but careful to hit the marks on the studio floor for the sake of the cameras.

As Ed encouraged and the studio audience cheered, these paisani achieved citizenship by merely spinning plates or walking the high wire. "Americanization is a vaudeville act," the show proclaimed; "and the sooner you learn to accept that, the more likely you will succeed!" My cousin Pippo, fifteen years my senior, a Cupid-faced hustler who studied America for angles as if it were a pool table, put it this way: "Who's gonna be Ed's Golden Guinea this week?"

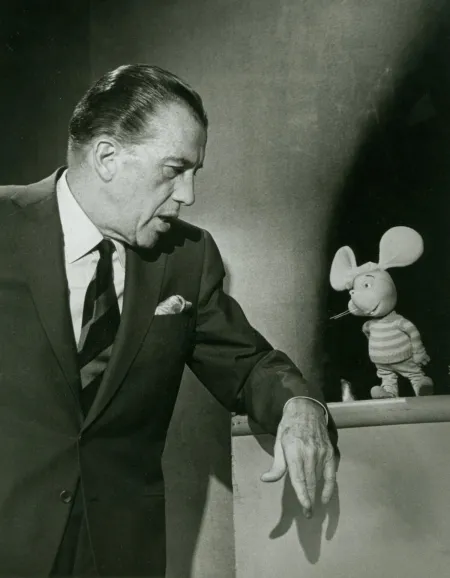

Many Italians contended for this title: Julius La Rosa, the boy wonder crooner whom Ed stole from Arthur Godfrey but later banned from the show for bopping chorus girls; Johnny Puleo, the harmonica player, a pint-sized Punchinello with a humped back and a hooked nosed; and of course Pat Cooper (born Pasquale Caputo), the skinny comic with the hornrims who looked and talked like a soda jerk moonlighting as a bank clerk. But the clear winner was Topo Gigio, a ten-inch, half-pound foam rubber puppet who became Ed's special mascot. If Dick Whittington had his cat, Ed Sullivan had his Little Italian Mouse.

Jack Babb, Ed's talent coordinator, had discovered Gigio while visiting Italy in early 1963. The chubby puppet was a regular on Carosello, the country's premier TV variety show. Dressed in a crooked cap and a striped jersey, Gigio was a recognizable type: the timid Italian schoolboy, the class runt who only wants his mother, always fears a pounding, and whose only defence is a coy innocence. ("Gigio," significantly, is a contraction of "gigione," ham actor.) Gigio had large, expressive eyes . . . and even larger and more expressive ears, which twitched at the slightest provocation. His nose constantly sniffed the air for trouble, and his plaintive, singsong voice—pitched halfway between an oboe's and an elderly country widow’s—forever moaned, "Ahi, Mamma!" Whenever threatened or confused, which was invariably, Gigio would roll his eyes and tremble as if he were about to wet himself.

But this calculated helplessness masked tenacity and subtle social commentary, not unlike the children's literature of Carlo Collodi. Many of Gigio's skits targeted political problems in postwar Italy and were based on Aesop's fables. My favorite childhood relic is a 45 recording of Gigio in an update of "The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse," which also satirizes Italy's infamous apartment shortage and traffic jams. When an alarm clock goes off in the Town Mouse's flat, Gigio, his country cousin, exclaims, "Ahi, ahi, i pompieri!" The firemen!

Babb didn't care about Aesop and social commentary. He was bowled over by the technology. Gigio was state-of-the-art. Unlike other marionettes at the time, Gigio was controlled by wands, not strings, a precursor of Jim Henson's Muppets. Three expert puppeteers, garbed in black hoods and black velour jump suits, operated Gigio with their own hands and three-inch rods. Maria Perego, Gigio's creator, moved the little mouse's feet and controlled his mouth. Frederico Gioli guided Gigio's hands and his wife, Annabella, manipulated those marvelous ears. But the TV audience couldn't see these intricate workings because of a black backcloth that made the puppeteers practically invisible. Meanwhile, character actor Giuseppe Mazzullo stood offstage and provided Gigio's voice.

When Ed studied the kinescope Babb had shot, he was impressed. The puppet act was perfectly synchronized, and even in close-up the camera could not spoil the illusion. Enthused, he booked Gigio to appear on the show April 14. Naturally, Ed made some changes. First, he insisted on calling the puppet "Topo," not "Gigio." "Gigio," he maintained, sounded too much like "Gigi," which Ed considered "a floozy name," or "Jesus," which might offend the good folks in the Bible Belt. Next, he instructed the Italians to eliminate the social commentary. Americans weren't interested in social commentary, he said. Keep it cute and light. After all, this was television. "So let's have a rrrrrrrrreally big shoe!" he said.

The Italians stared at their feet, wondering if they should call that cobbler in Brooklyn, but were too shell-shocked to protest. Compared to their poky network back home, CBS was as confusing as the Battle of Caporetto. To further complicate matters, none of them, with the exception of Mazzullo, spoke English. This language gap drove the CBS production crew nuts. The skit's proper coordination depended on Ed's saying the right thing at the right time, but since Ed seldom said the same thing twice, explained the floor manager, this was about as reasonable an expectation as relying on the Italian train system without Mussolini.