Jostled by the crowd overflowing the train station, Giuseppe Verdi stands beneath Columbus’s statue in Piazza Acquaverde, one eye fixed on Enea the fish peddler, the other rereading Regina Tumeo’s letter. Like Prime Minister Crispi, she is a word-drunk Sicilian: “. . . so I beg you, Maestro, as a young Italian mother (‘Three mackerels, not two, Enea!’), please write a little tune for my son’s birthday (‘Big ones! Not those sardines!’)—just as you wrote that lovely Pieta, Signore two years ago for the earthquake victims at Messina. (‘Oh yes. Bad business, that. Enea, mind the flies!’) Please, Maestro. You are a second father to Attilio. Your name is the first word he spoke. Your music is always on his—”

A fat, red-faced porter carrying luggage bumps into Verdi and tears the letter from his hand. It flies across the piazza, lands in a puddle, and is trampled by carriage horses and pedestrians.

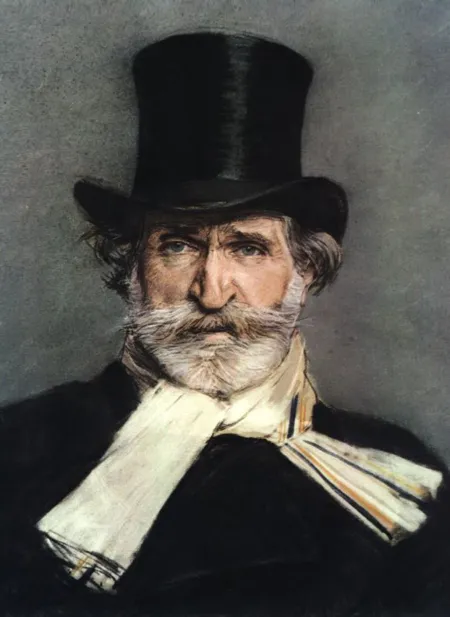

“Blast,” says Verdi. Enea smirks. Verdi taps his cane on the pavement. “Just take care of the mackerel, and no monkey business with the scales.” Verdi checks the clock on the facade of Principe Train Station. Two griffins guard a dial which reads 5:35. Verdi resets his pocket watch, always slow, and proctors Enea as he weighs the fish. In the waning light the old composer glances up at the statue of Columbus. Genoa’s favorite son is portrayed in all his youthful vigor, leaning against an anchor. Even in late afternoon his face radiates confidence and innocence. But his right hand rests in a vaguely exploitive way on the shoulder of a naked young woman, kneeling at his feet. Verdi winces but he remains fascinated by the determined look in Columbus’s eye, as if the explorer can see beyond the train station and commuters to some private horizon. In the harbor of Genoa floats a forest of masts.

“What the hell is he staring at?” mumbles Verdi.

"America, what else?” yawns Enea, a stumpy, carp-lipped lout in a leather cap and green apron. A tacked reproduction of Bronzino’s portrait of Andrea Doria as Neptune distinguishes his stand from the others crowding the square. During Carnival, Enea himself dresses as Neptune and roasts eels on a trident. Such showmanship makes him popular with the American tourists. Enea prints and distributes leaflets with Columbus’s face in hotel lobbies, gives tours of the dock, sells second-hand Baedekers. Red, white, and blue, as well as red, white, and green, bunting decorates his stand. His efforts have paid. Enea owns a dozen stands throughout the city, operated by overworked boys. A bill wad bulges his apron and makes refined girls blush. He wears fresh shirts, second-hand cravats, pressed trousers, and smokes Virginia cigarettes. Whistling, he wraps Verdi’s fish in week-old newspaper: “MASSACRE AT ADOWA!”

The Maestro quakes. Between outrage over the stupidities of imperialism and the struggle to compose that blasted Te Deum, his mind for days has rumbled like a volcano. But bemusement calms him as he again regards the statue. The allegorical nude reminds him of that American girl, Blanche Roosevelt. Suddenly, he furrows his brow and blinks at Enea.

“America? But isn’t America the other way?”

Enea gestures to the tourists in the square. “For me, Maestro, America is here. Wherever they spend their money is America.”

“Very clever. But seriously, Enea,” and the old man’s expression becomes vague and vulnerable, “east or west?” One of the few private facts Verdi keeps from the press are the tiny strokes he suffers. His constitution is still so resilient, however, that a cup of espresso, very black, usually rallies him. Only the astute can tell his strength is failing.

With a merchant’s tact, Enea says: “Who knows, Maestro? These are confusing times.”

“Yes,” says Verdi, his expression again alert and truculent, “we’ve lost our bearings.” He addresses the statue of Columbus: “We need a compass, Admiral.”

“Our troops needed a compass,” Enea grumbles. “Those black bastards slaughtered us.”

“We’re the bastards,” says Verdi, “tyrannizing Africa! We were wrong, and we paid for it!”

My God, the shame! How can he write a Te Deum after Adowa? The very name sounds like a bad opera. Crispi was Garibaldi’s secretary and aide de camp, and he plays the Pharaoh? Not so fast, Peppino. The Khedive commissioned Aida for the opening of the Suez Canal, remember? He sent you two ebony chairs and an ivory baton. They’re with your other trophies at Palazzo Doria.

Yes, yes, but Aida was a tragedy. Not even Rossini could have written a farce like Adowa.